When It’s Not the Tooth’s Fault!

- Dec 1, 2025

- 4 min read

Distinguishing Odontogenic from Non-Odontogenic Pain — and Why Misdiagnosis Matters

(Summary of lecture given to Alpha Omega London October 2025)

A presentation by

Dr Leigh-Ann Elias BChD, DipOdont (Oral Surgery), MFDS RCSEd, MSc (Maxillofacial & Oral Surgery), MOralSurg RCSEdSenior Clinical Teacher, King’s College London

Dr Leigh-Ann Elias delivered a compelling and highly informative lecture on the complexities of orofacial pain, highlighting the crucial distinction between odontogenic and non-odontogenic pain and the potentially serious consequences of misdiagnosis. Her talk underscored the central role dentists play in identifying, managing, and appropriately referring patients with facial pain—conditions that often present deceptively like common toothache.

The Brain’s Interpretation of Pain

Dr Elias began by revisiting the classic neurological concept of the homunculus, the distorted brain map that illustrates how much cortical space is devoted to different body regions. Because the mouth and face occupy such a large proportion of this map, even minor oral lesions can produce disproportionately intense pain. Modern high-resolution MRI has deepened our understanding of these pathways, allowing clinicians to appreciate why facial pain can be so severe, persistent, and complex.

Pain perception is not merely a response to tissue damage; it is an interaction between peripheral signals and central processing. The trigeminal nerve, with its powerful and direct pathways to the brainstem, amplifies this effect. This explains why conditions such as temporomandibular disorders (TMD), trigeminal neuralgia (TN), and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) are so debilitating—and why they are so often mistaken for dental pain.

The Nature of Pain: When the Alarm Misfires

Dr Elias described pain as the body’s alarm system: ideally, it should activate only when genuine danger exists and stop once healing has occurred. Problems arise when the “alarm” continues to sound without cause, or long after the tissue has healed. This conceptual model helps differentiate key pain categories:

Odontogenic pain: arising from teeth or supporting structures.

Post-traumatic neuropathic pain: persistent after dental treatment or injury.

Idiopathic pain: present without identifiable cause.

Sinogenic pain: referred from the maxillary sinus.

Cervicogenic pain: originating from neck or muscular sources.

Many patients experience more than one pain type simultaneously, making careful assessment essential. Clinicians must remain alert to systemic or life-threatening causes of facial pain—including cardiac conditions or tumours—particularly when symptoms do not match typical dental patterns.

The Essential Role of a Detailed Pain History

A meticulous history is the clinician’s most powerful diagnostic tool. Dr Elias emphasised exploring the nature, onset, duration, triggers, relieving factors, and functional impact of pain. Patients often report multiple pains, so determining the dominant one—“If you could remove one pain with a magic wand, which would it be?”—helps focus the diagnostic process.

Recognising pain quality is equally important.

Neuralgic pain is sharp, electric, or shock-like.

Neuropathic pain is burning, tingling, or aching.

Family history may reveal genetic predispositions such as migraine, which frequently runs in families. Stress, hormones, dehydration, and sleep disruption commonly exacerbate these conditions. Autonomic symptoms—including tearing, eye redness, nasal congestion, or facial sweating—suggest TACs rather than migraine or dental pathology.

A comprehensive dental, medical, social, and psychological history is essential, as emotional stress, isolation, and significant life events can amplify pain perception. Dr Elias encouraged clinicians to approach mood and psychological wellbeing with sensitivity, recognising the close connections between mental health and chronic pain.

Examination: Correlating History With Findings

A structured examination should include:

Full cranial nerve assessment.

Mapping altered sensation to identify nerve involvement.

Examination of the TMJ and masticatory muscles.

A complete dental examination with percussion, probing, and palpation.

Evaluation for muscular pain, noting that Botox combined with stretching exercises can be effective for TMD and migraine-associated muscle tension.

Crucially, imaging should be used judiciously and only when it supports a well-formed clinical hypothesis. Scans are not a substitute for thorough clinical assessment.

Understanding Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is now recognised by the WHO as a disease in its own right. It affects around 20% of the population and carries a significant personal, social, and economic burden. Importantly, pain intensity is shaped by expectation and context. Classic examples include a man screaming because he believed a nail had pierced his foot—when in fact it had not—and soldiers reporting little pain from major injuries during combat. These cases illustrate that pain is created and modulated in the brain, not simply generated in tissues.

Common Orofacial Pain Conditions

Post-Traumatic Neuropathy

Often follows dental procedures or facial trauma. Presents as burning, tingling, or aching sensations, sometimes with numbness. A short “pain-free window” immediately after waking is highly characteristic. Imaging frequently appears normal; education and long-term management are key.

Trigeminal Neuralgia (TN)

TN produces sudden, electric-shock pain in the V2 or V3 region, triggered by eating, speaking, brushing teeth, or even light touch. Local anaesthetic can provide immediate relief and help confirm the diagnosis.

Key points include:

Carbamazepine is first-line therapy.

Risk of Stevens–Johnson syndrome is higher in certain genetic populations.

Classical TN often results from vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve.

Microvascular decompression offers excellent long-term outcomes but carries surgical risks.

Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias (TACs)

Cluster headaches are the most recognised TACs. They cause intense orbital pain with tearing, redness, nasal congestion, and ptosis, often waking the patient from sleep. High-flow oxygen and intranasal triptans are highly effective. Steroid or indomethacin trials assist diagnosis.

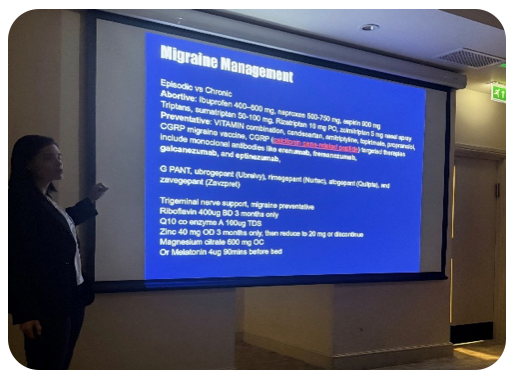

Migraine and Orofacial Migraine

Migraines can present as toothache or jaw pain, leading to unnecessary dental treatment. Stress and dental procedures can trigger attacks. New CGRP inhibitors such as Erenumab offer major benefits, while nutraceuticals—including riboflavin, magnesium, zinc, CoQ10, and melatonin—provide safe adjunctive support.

The Psychological Dimension

Chronic facial pain significantly impacts emotional wellbeing. Patients with anxiety, depression, or poor coping strategies are more vulnerable to prolonged pain. Dr Elias highlighted the importance of psychological support, noting that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is especially effective for chronic pain and can reduce medication use by up to half.

Despite concerns in the media, medications such as gabapentinoids remain valuable for selected patients. Botox is an underused but potent option for neuropathic facial pain, particularly when local anaesthetic offers temporary relief. Pharmacogenomic testing shows promise for tailoring medication choices, though it is not yet widely available on the NHS.

Holistic measures—nutrition, hydration, exercise, sunlight, rest, and spiritual wellbeing—profoundly influence inflammation, mood, and pain resilience.

Dr Elias delivered a rich, nuanced, and expertly structured overview of orofacial pain and its many mimics. Her insights equip clinicians to make safer, more accurate diagnoses and prevent unnecessary treatment.

Alpha Omega extends its sincere thanks for her time, expertise, and generous contribution to our educational programme.

Comments